In 2011, I proudly developed and taught a new graduate course at Georgia State University named “Introduction to Modeling for the Life Sciences”. I took a bunch of students from six different academic departments and threw them into the deep end of studying the application of mathematical modeling in the life sciences. And I don’t mean the typical basic stuff you usually show newbies like elementary statistics, linear regression models, or remedial calculus. I wanted to discuss big questions such as:

- How can a non-mathematican tell a possibly good model from a bad one?

- How can a mathematician make sure they are building a reasonable model that will satisfy scientific domain experts?

More specific questions we dug into were:

- How can we assess the modeling methods of the Blue Brain Project?

- What kinds of models of the brain can there even be? And why are there so many?

In reference to my promotional materials to attract students to my intimidating-looking course description and reading list, we also considered more cryptic questions such as:

What is the connection between (a) the ability of an F-16 fighter jet to maneuver much more nimbly than an F-4, (b) the possibility that small genetic modifications lead to large differences in phylogenetic outcome within a couple of generations, and (c) the ability of a neural circuit controlling limb motor patterns to switch an animal rapidly between locomotive gaits?

Now, of course the goal was not for my students to really understand these technical papers in depth. But most of these trainee scientists and philosophers had future plans to be involved in science in some way, and as such they needed some preparation in the emerging ways that computing is reshaping scientific understanding. Is there a middle ground to understanding such literature without abandoning it for purely popularist science journalism about the topic?

I recently discovered a dead link on the class page for our crowning achievement: a collaboratively-written document produced by the students, with my help, that summarized their high-level understanding of a pretty complex mathematical model.

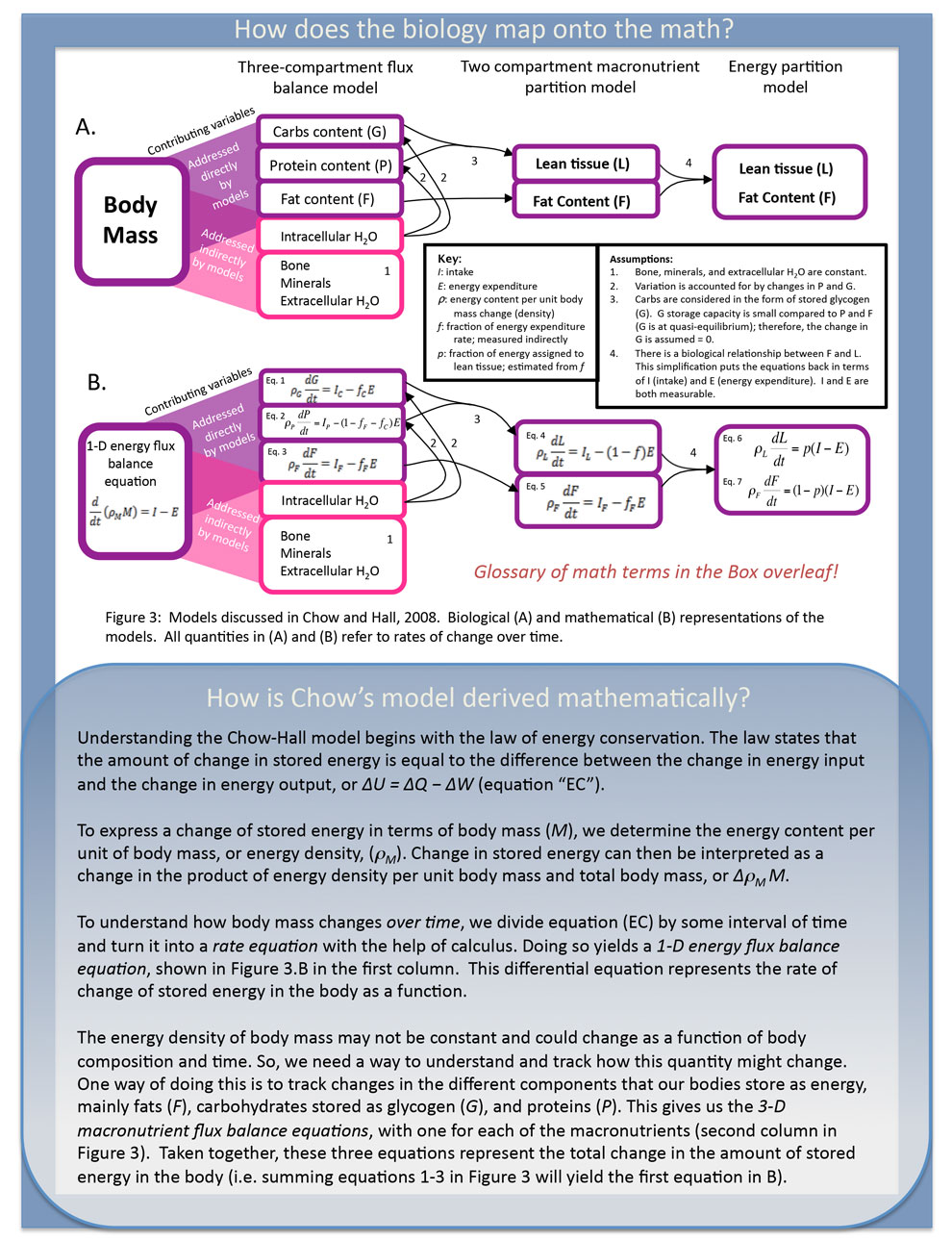

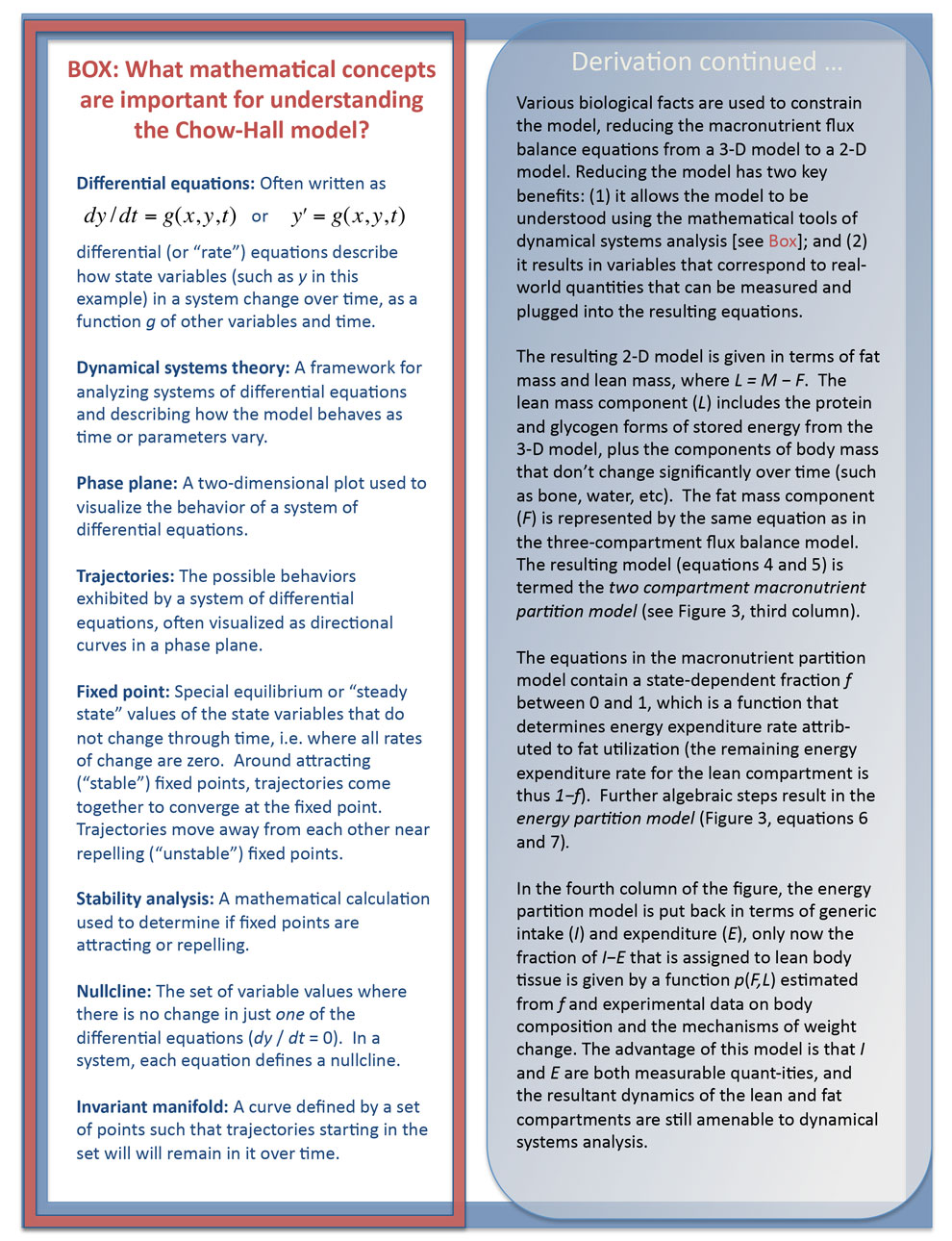

My students spent about three weeks dissecting Carson’s influential 2008 paper with Kevin Hall, which uses principles of qualitative dynamical systems in the form of analysis of fixed point stability and phase-plane diagrams. Nonetheless, the assumptions and derivation of the differential equations is, of course, not at all trivial. I invite you to take a look first – it’s open access.

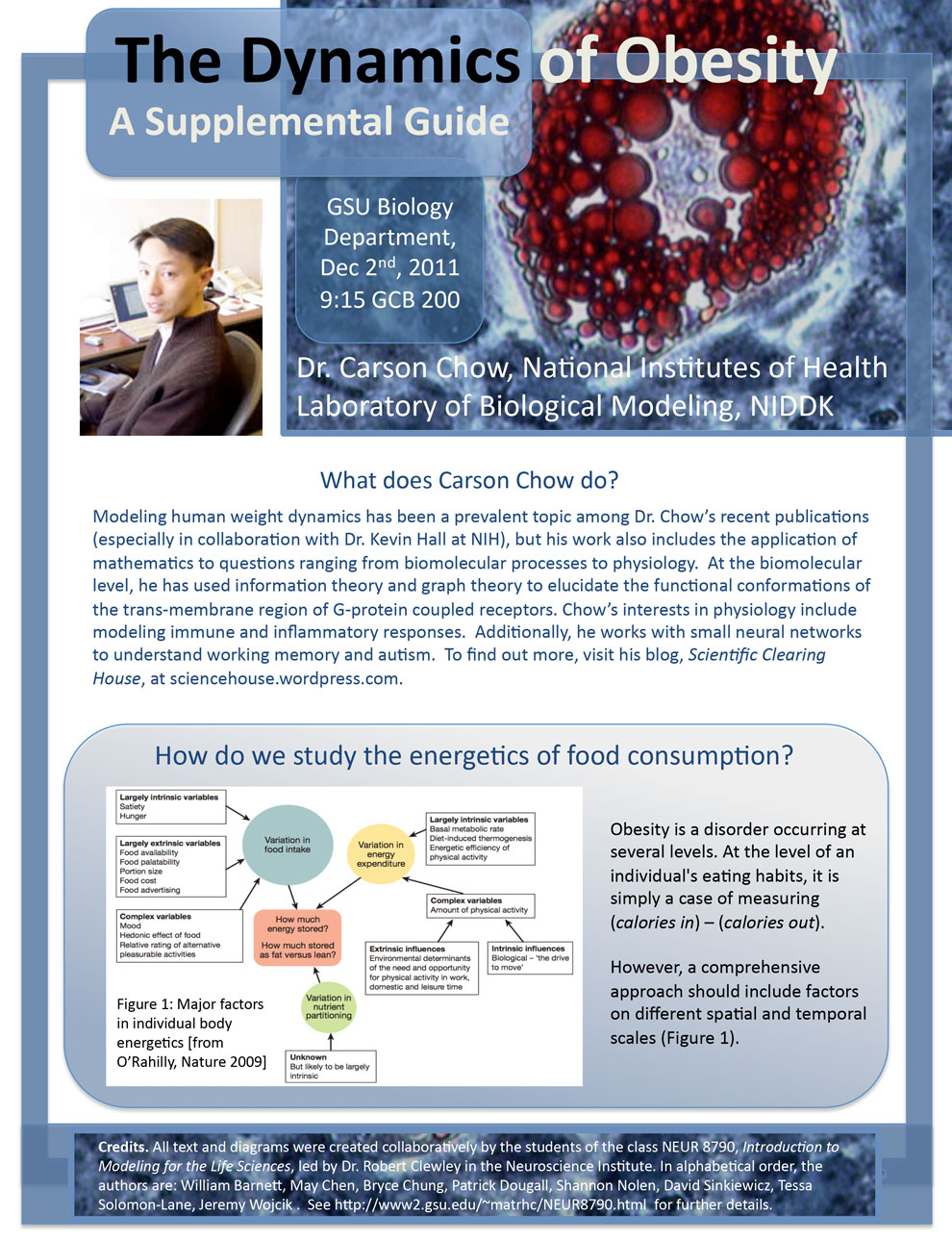

The document produced by my students was used as a handout to accompany a public lecture given my friend and colleague, Carson Chow, visiting from NIH. I’d invited him to speak at GSU on “The Dynamics of Obesity”.

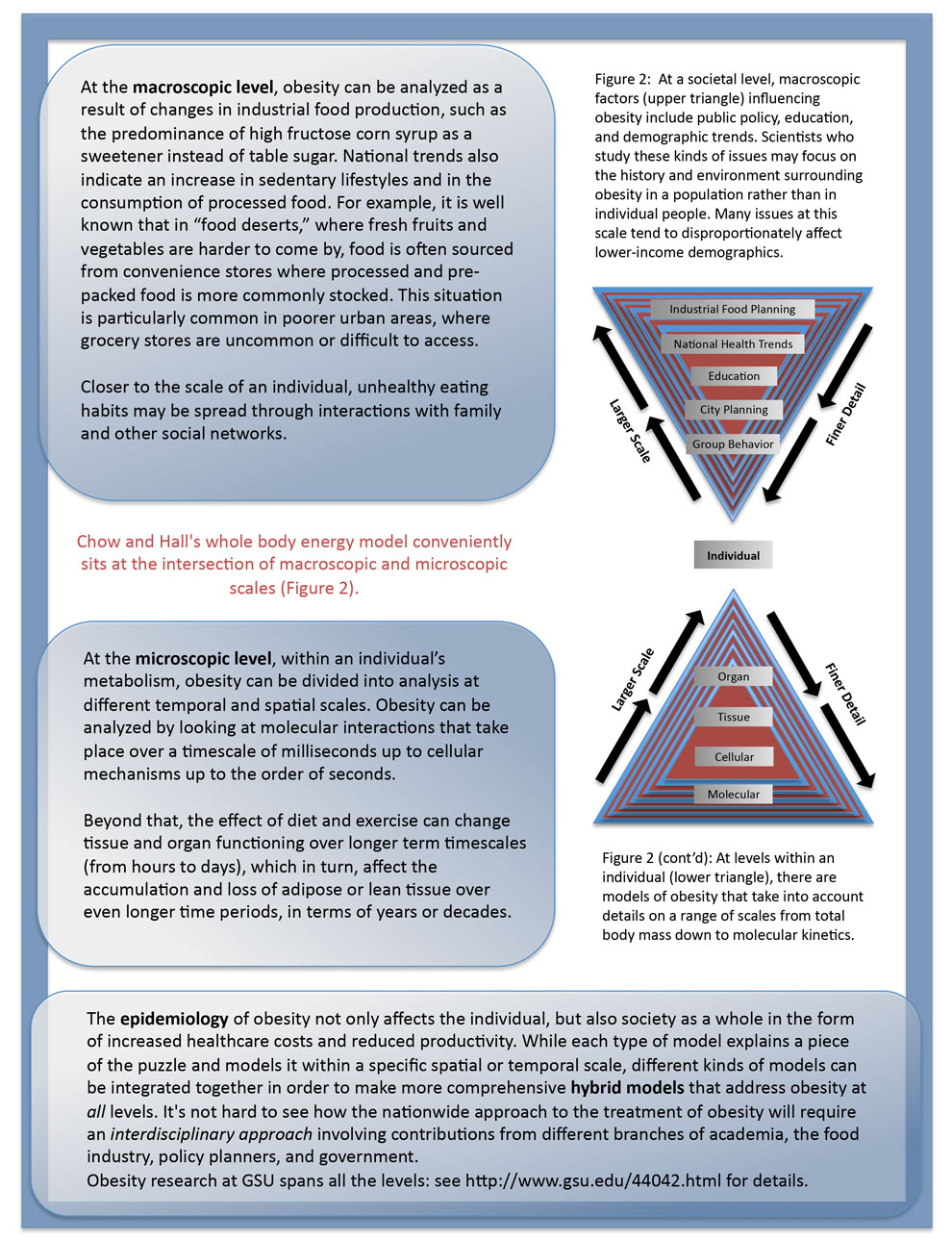

I thought I’d share this handout with you by embedding the pages here. Now that I’m expending more effort at the interface of technical and non-technical users and readers, this seemed highly relevant. I think it’s a good example of using a mixture of diagrams, math, and prose to explain the technical basis of the work as well provide adequate context to the assumptions and literature surrounding it.

(Link to the original, high-resolution PDF.)

I’ll let the value of the handout speak for itself. I think the students did a great job in expressing complex ideas without dumbing them down by organizing information into small, inter-related chunks, and making mathematically meaningful diagramatic representations.

The students graduated from the class with a lot of valuable, broad insights into the world of real-world math modeling. Not everyone has the time or interest to learn dynamical systems modeling to a high degree of technical proficiency. There are not enough articles in popular science magazines that dare to delve this deeply into (relatively) complex mathematics such as this when it has clear application in experimental science, but in the right hands I don’t think it’s so difficult to present a fair overview of the ideas.